When did you first become interested in the world of art, especially in calligraphy?

This is quite a difficult question to answer, because I have spent most of my life painting. So today, at 84 years of age, I have actually been painting for more than 60 years. It’s true that during the first 10 years of my career I painted with a relatively free theme and my paintings were more academic in nature. In 1969, I had the chance to go to the USA with one goal in mind: to learn as much as I could about graphic design so that I could then introduce this into the Indonesian art world. During my time there, amidst all the studying and practise, I encountered a particular challenge as a painter. I was quite agitated when I tried to find out the answers to these following questions: “Who am I?” and also “What is the true face of modern Indonesian art?” My agitation reached its peak when I stayed in New York. When I was in Manhattan, I visited hundreds of galleries there, and always came up with the same questions, “Who is A.D. Pirous?” “If you’re a painter, then what kind of painter are you?” “If you consider yourself as an Indonesian painter, where is the proof of that?” These self-questions were not properly answered at that time.

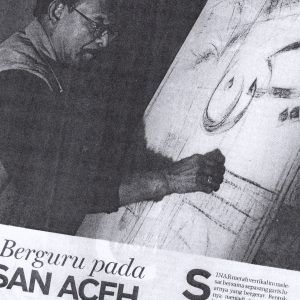

One day there was an exhibition in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) on Fifth Avenue, New York. The theme was traditional and modern Islamic art from the Middle East and North Africa. Almost all of the works of art on display featured some sort of calligraphy. The first time I saw the exhibition, something stirred in me because what I saw was somehow very familiar to me. It brought back memories of my childhood in my hometown of Aceh where tombs, mosques and the holy Al-Quran were all decorated with calligraphy and were widely spread around the community. I felt that this was an influential part of my life that resurfaced in New York, after years of feeling disconnected because of my settling in the academic world, which is much more internationally oriented.

At that time, I thought that maybe this was what I had been searching for all that time after wandering around the world and getting lost in the western way of thinking in terms of art. I felt that I had finally found a place to set my footing – a place which I had forgotten for so long. At that time I made a promise to myself that should I return to Indonesia I would develop calligraphy as an art form and make it an important, structured part of my modern paintings in a systematic way in order to answer all my questions.

What exactly did you see there that could cause such a stir in your soul?

When I left for New York, I had a strong belief that I would not be influenced by the western culture. But I also didn’t pay much attention to being an Indonesian either. But there I found out that everyone was compelled to explore and showcase their roots. I saw a Japanese modernist artist creating a very modern and abstract-style painting that still depicted his Japanese roots in the form of Zen Buddhism. The same can be also be said about Korean or Indian artists. Then, when I asked myself the question, “Where exactly is Indonesia?” I was somehow reminded of my roots. From that faraway place, I could view my hometown with a clearer perspective. Then, after attending the exhibition at The Met, I became more convinced that this was the world and the personal identity that I had been looking for.

When did you start to establish your focus in the calligraphy art world?

When I was in New York, in addition to preparing the graphic design lessons that I would introduce in Indonesia as a new discipline, I also took a minor in graphic art through print making. For the first time, in a studio in Rochester, New York, I tried to apply calligraphy as a visual art form. I was determined that if I had the chance to return to Indonesia, I would consider this as the path I would take in my effort to make a contribution to the Indonesian art scene.

I got back to Indonesia in 1971. As soon as I arrived in Bandung I left all my belongings and continued my journey back to my hometown of Aceh to visit the ancient tombs and other historical places dating back to the Islamic Kingdoms of the 16th and 17th century. I did a lot of research and analysis and took plenty of photos during my year there. And then, in 1972, upon my return to Bandung I immediately staged my first solo exhibition in the lobby of the Chase Manhattan Bank, Jakarta, with calligraphy as the theme. I believe it was the first time ever that a solo exhibition with the theme of Islamic calligraphy had been held in Indonesia.

And what was the response of the art world at that time?

My artist friends from all across the archipelago supported me and asked why I did it, to which I answered, why not? I reasoned that 80-90 percent of Indonesian people follow Islam. I also saw the clear link to Islamic culture so, when I first showed these calligraphy paintings, I felt sure that the majority of our people would have an instant familiarity with this art form. Since then, the art of calligraphy painting has been unstoppable and is still developing even to this day.

How has calligraphy painting developed and evolved since you introduced it in 1972?

In the beginning I was really enthusiastic with the pace of development. From only a single person, it soon multiplied into 2, 4 and then 10’s of people until, in 1979, there was a major exhibition of Islamic calligraphy painting in Semarang. Many famous names in the national painting scene such as Affandi, Achmad Sadali, Amang Rahman Jubair, Amir Yahya, Batara Lubis, and many more, took part in the exhibition. That was very heartening. However, during the following decades, especially for me, dabbling directly in the painting world, I kept asking myself “where are we now” and “where do we stand in the calligraphy painting world?” From what I see, I have to admit that I am deeply saddened because what I see is not what I had imagined before. I had imagined that the development of modern calligraphy painting in Indonesia would be enlivened with creative new inventions. I had imagined that every year there would be changes or breakthroughs in its expression, things which almost never happen nowadays.

Why didn’t this happen?

I know that to become a painter it is not enough to only depend on the talent that you have. A painter should also be equipped with a staunch heart and unwavering mind. In other words, a painter should be smart and have a constant desire to add to his knowledge, to enrich his vision and mission in conducting art through extensive reading, viewing and discussion. Without these things, he will be trapped in a repetitive circle. The way I see it, some of the calligraphy artists here are fascinated purely with their own talents and abilities. It’s as if after they quote from the holy verses of Al-Quran or hadiths, then their work is done. For me, in the first 10 years of my career this condition was tolerable. But afterwards I realized that this was not the way to go. From my experience, I have come to realize that calligraphy as a vessel is getting more and more limited in movement. It is used only as a communication means with a spiritual and religious theme while actually I see calligraphy as letters that link our thoughts through the use of words, sentences or philosophies. Letters are the vehicle of civilization. This is the comprehensive meaning of calligraphy because it not only provides a service for religious thoughts but also for life itself, social and economic, for science, literature and many other things. All aspects of our lives can be summarized in the revelation of letters, forms, sentences, slogans, philosophy, and sufistic sayings. Therefore, calligraphy is actually a vehicle that should move in various directions.

How did you get out of the calligraphy zone which many people think only as an Islamic spiritual art?

Today, I still quote verses from the Al-Quran and hadiths but for a few years now I have tried to do more than just that. For instance, when I turned 70 in 2002, I tried to take on several political themes that were inspired by the violence in Aceh. At that time I launched my criticism towards both conflicting sides—those in Jakarta as well as the people of Aceh. I stated that the conflict in Aceh could not be solved by violence, but rather by sitting together and talking. At that time I created themes which I took from the literary tale The Chronicle of the Holy War (Hikayat Perang Sabil). I presented the paintings as an important installation at the front of the exhibition room in the National Gallery, conveying the message that calligraphy no longer merely bears a religious mission but also has a spirit to be free and to show some self-esteem.

From that point, I developed calligraphy further into other fields, including sayings, holy verses, quips from literature, and social issues - and my calligraphy paintings do not only use the Arabic alphabet. It is more fun for me if more people can understand my calligraphic paintings. The communicative element becomes more important for me. As I get older, I feel that I am not actually doing art, but rather I am expressing who I am through art. What I am doing does not always have anything to do with the aesthetic but nevertheless I just want to express my ideas. This is what I want to say, this is how I feel because this is what happens around me. So they are like notes that I want to share with others. So for me, paintings are not something that involves only aesthetic beauty but also something that includes moral and ethical messages. Therefore, I would very much prefer people to enjoy my works not because they find the colours enticing, but because they can understand what I mean and they can feel what I feel through them.

I have noticed that painting art, and the process that goes with it, is still going strong just as it has been for hundreds of years and probably will stay strong for the next hundreds of years despite the stronghold of technology. Do you think that the concept of ‘timeless’ has penetrated into the world of art?

We know that there are millions of painters around the world, but only a few will ever see their works in museums. So we have to simply ask, what is a painting? Is it only achieved from the formation of shapes, lines, pictures, proportions and colours, or is there something else at play? From my experience, after many years in the world of art, I believe that painting art does not only convey a meaning through visual techniques. A good painting is able to explore the problems of the ages, the zeitgeist of a period of time, which we record with our abilities and intellects and then immortalize in works that can be viewed and re-viewed any time we want, all the while evoking the spirit of the time when the works were created. These magnificent works hanging in museums across the world enable people to see just that, bringing them back to the times when the works were produced, retelling the spirit of the ages at that time. When a work can achieve this, then that is what I think is a ‘timeless design.’ One of the greatest examples of this is the ‘Guernica’ by Pablo Picasso.

Author

Anton Adianto graduated from Parahyangan Catholic University majoring in architecture. His passion for writing, watching movies, listening to music, uncovering design, exploring the culinary world, traveling, delving into the philosophy of life, meeting people and disclosing all matters related to technology feeds his curiosity. Currently he resides in both Jakarta and Bandung.

PAMERAN ARSIP ARTIKEL #1

Jl. Bukit Pakar Timur II/111

Bandung, 40198

Indonesia.

Hours

Tuesday – Sunday:

10:00AM – 5:00PM

+62 22 2530966

(office hour only)